“How Did We Get Here: Growth of Federal Student Loans” follows the expansion of the federal student loan program throughout the years, from its origins in helping middle-income students afford a college education to an eventual rise in student loan borrowing. This 15-minute film chronicles:

6 Decades The first federal loan program, the National Defense Student Loan, now the Perkins Loan, was created in 1958.

43 Million Outstanding Loans 1 in 6 American adults today has some kind of student loan debt.66% of first-time bachelor’s recipients borrowed for their educations in 2007-08, up from 49% in 1992-93.

RUNTIME: 15:16 Download Our Viewing Guide Read More Below Watch Chapter 2 VideoWe’ve seen an interesting evolution in terms of the student loan programs—from creating greater access to loans to ensuring that defaults don’t happen, to what we have now, which is this interest in debt.

Jamie Merisotis, President and CEO, Lumina FoundationExecutive Director, National Commission on Responsibilities for Financing Postsecondary Education, 1991–93

Establishing LoansFederal student loans have their origins in efforts to help middle-income families afford a college education.

Massachusetts Higher Education Assistance Corporation (MHEAC) started a guaranteed student loan program in Massachusetts, which insured students’ bank loans with money raised through philanthropic donations from local businesses. This program provided a model for a future federal student lending program.

The National Defense Education Act (NDEA) created the National Defense Student Loan (NDSL) Program, the first federal loan program, now called the Federal Perkins Loan Program. Distributed to students by institutions, these loans required a monetary match from institutions.

The first Higher Education Act (HEA) created Guaranteed Student Loans (GSL), a public-private partnership with the federal government subsidizing capital from banks to provide loans to low- and middle-income students.

The extent to which people should be relying on loans, and the extent to which they should be subsidized by the government, is something that we’ve come to not by design so much as by accident and political dictates and the dictates of the federal budget.

Sandy Baum Independent Consultant

In the 1970s, federal loans quickly rose in volume due to the rise of college costs, creation of government-sponsored enterprises, establishment of state loan guarantee agencies, and expansion of loan eligibility and limits.

The HEA Reauthorization Act created the Student Loan Marketing Association (eventually Sallie Mae), originally to add liquidity to the GSL program by buying loans from lenders to add more capital.

HEA Reauthorization provided incentives for states to establish loan guaranty agencies, which insured federal student loans made by lenders.

The Middle Income Student Assistance Act (MISAA) eliminated the income requirement for student loans, allowing middle- and high- income students to qualify for loans. The act was repealed in 1981, but other income expansions followed.

As part of the 1980 HEA reauthorization, the PLUS program was created to allow parents to borrow for their children’s education.

The Omnibus Reconciliation Act repealed MISAA, replaced the PLUS program with Auxiliary Loans to Assist Students (ALAS) and extended borrowing to graduate and independent undergraduate students. It also imposed borrower loan origination fees on new loans.

It began to really grow in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and with the growth came a whole series of problems. David Evans Professional Staff

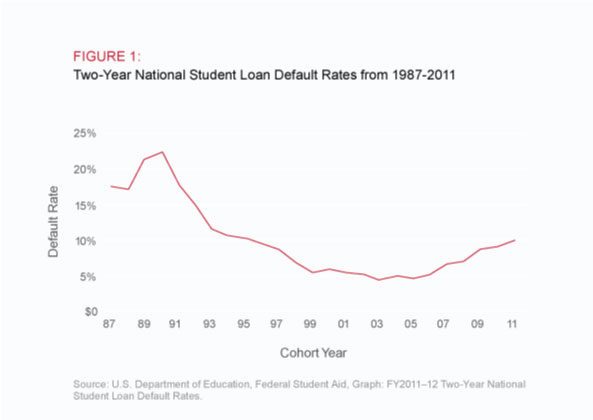

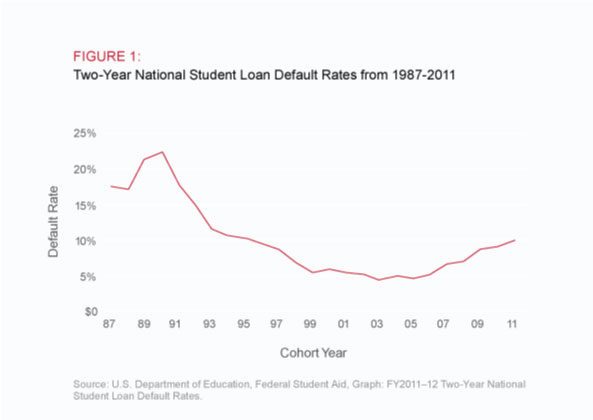

Concerns about default rates on student loans led Congress to implement a number of policies meant to reduce these rates.

The HEA Reauthorization of 1986 added provisions prohibiting students in default under GSL from receiving new federal loans. It also gave the Department of Education more power to regulate student loan lenders. It split ALAS into the Supplemental Loan to Students (SLS) for graduate and independent students and brought back PLUS loans for parents. It also created consolidation loans, but borrowers who had different lenders could not consolidate (known as the single holder rule).

The Cohort Default Rate was established, eliminating student borrowing eligibility at schools with high default rates for three consecutive years. The way this is calculated has changed over the years.

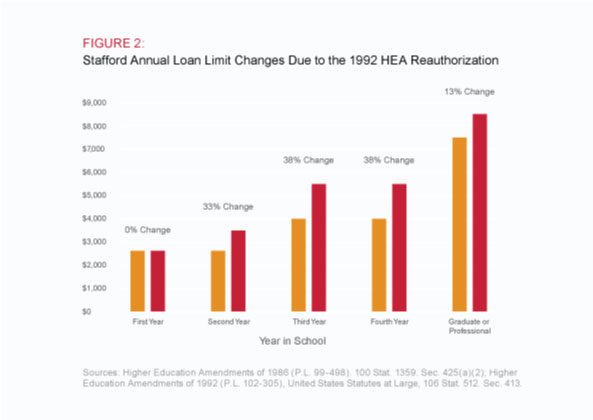

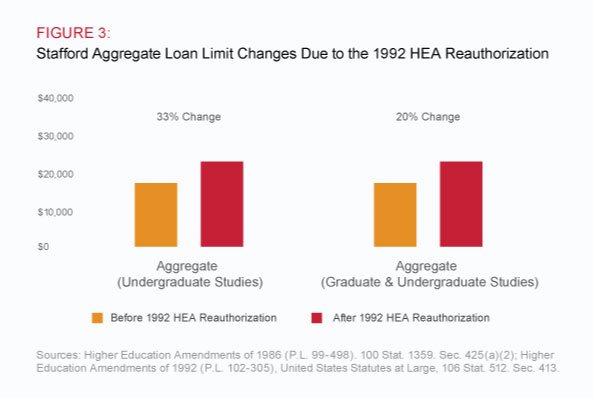

In the 1992 HEA Reauthorization, direct lending was introduced through a demonstration program that made unsubsidized Stafford loans available to all students, and removed annual and aggregate borrowing limits on PLUS loans. This act also restructured Stafford loans and PLUS loans into the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program.

We finally got to the point, in the early ‘80s, when the volume was so great, people for the first time began to worry about A.) default rates, and B.) cost to the government.

Thomas Parker Co-Founder and President,

As limits on borrowing were increased and college costs were rising, many students were having trouble repaying loans through the standard repayment plan.

The 1993 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act formally called for a phasing-in of the Direct Loan Program to begin in 1994. It also established Income-Contingent Repayment, Extended Repayment Plan, and Graduated Repayment Plan for Direct Loan Borrowers.

The Income-Sensitive Repayment Plan for FFEL borrowers was established, allowing FFEL borrowers to be eligible for extended and graduated plans.

The Higher Education Reconciliation Act allowed for professional and graduate students to borrow through the PLUS program.

The Emergency Appropriations Act repealed the single holder rule, allowing borrowers to consolidate loans between lenders.

The College Cost Reduction and Access Act (CCRAA) established the Income-Based Repayment Plan.The Higher Education Opportunity Act (HEOA) mandated that cohort default rates be calculated to include students in default three years after entering repayment and that the U.S. Department of Education publish those rates. The Ensuring Continued Access to Student Loans Act (ECASLA) temporarily authorized the U.S. Education Department to buy loans from private lenders to ensure students had access to capital during the financial downturn.

The Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (HCERA) repealed the FFEL programs so that all new federal student loans–except for Perkins Loans—would be made directly from the government to students, saving administrative costs. The terms of the IBR are revised by Congress to lower the payment cap and forgive loans five years sooner than previously for a limited subset of students (those taking out their first loans after July 1, 2014).

The Obama Administration created the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) plan via executive order, extending more generous IBR terms to a larger group of borrowers. The Budget Control Act eliminated subsidized loans for graduate students.

The Obama Administration, via executive order, expanded the PAYE plan to individuals outside of the original 2011 scope to all borrowers with direct loans.

The idea of creating more lenient, more workable, more flexible repayment options became a very important priority and we began to see those incorporated.

Barmak NassirianDirector of Federal Relations and Policy Analysis

American Association of State Colleges and Universities, 1990–98, 2013–present